I read First and Second Maccabees so you don’t have to (but you should)

I wanted to write a blog about the myths surrounding Chanukah – how the story of the oil that lasted 8 days was added afterwards, because the Rabbis didn’t think it was fitting to celebrate a military victory, and how the Maccabees weren’t only fighting for religious freedom, but also were fighting Jews who were “assimilationists”.

But the articles I read in preparation were riddled with inconsistencies and contradictions, so I decided it was about time to read the books of Maccabees for myself.

As I explored in the last blog (Chanukah: A Holiday with no Holy Texts), The Maccabees aren’t part of Tanach – part of our canon – and so they’re not as easily found as our other texts. The Maccabee books are canonical for Catholics, though, so Catholics to the rescue: I read the translation provided by the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops (https://bible.usccb.org/bible/2maccabees/1 and https://bible.usccb.org/bible/1maccabees/1.

Here is some of what I found:

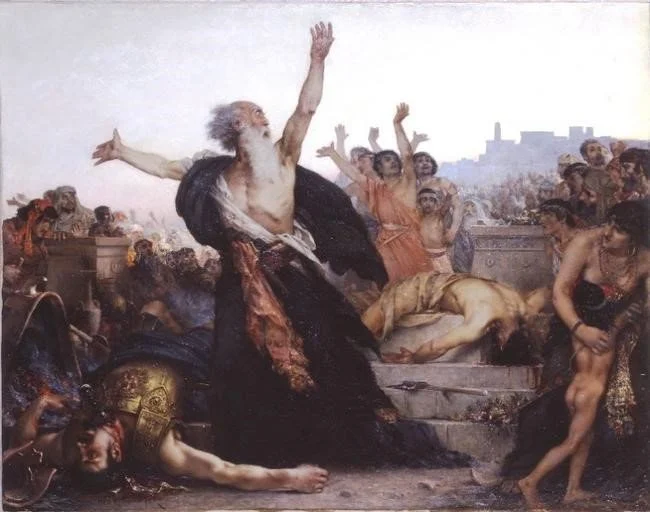

There is a lot of very graphic gore.

I am not going to catalogue it all here. Suffice it to say, First and Second Maccabees are a chronicle of war and conflict in all its cruelty, violence, suffering, and death, as much as they are a chronicle of the eventual victory of a small band of brave Jews who want the right to practice Judaism, over the large armies of powerful nations.

There are different reasons given for the celebration being eight days (and none of them have to do with oil)

Second Maccabees begins with a letter from the Jews of Jerusalem to the Jews of Egypt, reminding them to observe Sukkot in Kislev. You might assume that maybe they hadn’t been able to celebrate Sukkot, but chapter 10 tells us that they had – just not in the Temple. It says, they celebrated “remembering that not long afore they had held the feast of the tabernacles, as they wandered in the mountains and dens like beasts.” In other words, they celebrated for 8 days to celebrate that from that time forth, they’d be able to celebrate for eight days in the Temple.

But the book also tells us that when Solomon dedicated the Temple altar with its first sacrifices, he did so for 8 days, and since this was a rededication, it would also be eight days.

Why on the 25th of Kislev?

It’s the anniversary of when the Temple was first profaned by the idols and debauchery by the conquering king.

There is a story about flames, and it is miraculous, but it’s not the “miracle of oil”.

In 2 Maccabees we learn that, prior to exile, the priests had banked the fire of the altar to be reclaimed later. When they returned to get it, though, they only found a thick liquid, and the priest “ordered them to scoop some out and bring it.” After the material for the sacrifices had been prepared, Nehemiah ordered the priests to sprinkle the wood and what lay on it with the liquid. This was done, and when at length the sun, which had been obscured by clouds, began to shine, a great fire blazed up, so that everyone marveled. Nehemiah and his companions called the liquid nephthar, meaning purification, but most people named it naphtha.”

There’s a “red wedding”

When Judah dies, Simon and Jonathan take over leadership. One of the many, many tribes that they encounter kidnap another brother, John and takes all that he has with him (he was in the process of asking another tribe if they would hold a bunch of his tribe’s belongings while they were in hiding). They happen upon a huge wedding about to take place within that tribe. They slaughter most of them, the rest flee, and they take all the things left behind. The story ends, “Thus was the marriage turned into mourning, and the noise of their melody into lamentation.” (1 Maccabees 9:41)

There’s a Purim connection.

Several years after the Temple is restored, Judah defeats Nicanor, a general who has been by turns friendly and vicious. Finally, Judah defeats him on the 13th of Adar and “ordered Nicanor’s head and right arm up to the shoulder to be cut off and taken to Jerusalem”, along with other indignities:

“Judah hung Nicanor’s head and arm on the wall of the citadel, a clear and evident sign to all of the Lord’s help. By public vote it was unanimously decreed never to let this day pass unobserved, but to celebrate the thirteenth day of the twelfth month, called Adar in Aramaic, the eve of Mordecai’s Day”.

The story doesn’t end with the rededication of the Temple.

When we tell the story of Chanukah, we usually end with the “happily ever after” of that mythical oil burning for eight days. In the books of the Maccabees, there are many chapters after the Temple is restored, devoted to many years of war, attacks and counterattacks.

Sometimes the inter-Jewish conflict is framed as assimilationists versus religious Jews, but it’s also about martyrdom versus survival.

While at first, there are Jews who approach their occupiers and adapt or adopt some of their ways, there are other periods where Jews are threatened with death if they don’t convert, and circumcision and Jewish observance is outlawed. In the story that you may have learned about Mattathias killing a Jew who comes forward to make a pagan sacrifice, what’s often missed is that the man is doing so on pain of death. So, in addition to fighting for religious freedom, Matthathias and his family seem to insist on martyrdom over survival.

There’s even a story in 2 Maccabees where a man who is being forced eat pork, has the chance to have the pork exchanged secretly for something that is permitted, so that he will survive. He chooses not to – he chooses martyrdom.

There’s another story where a mother (said to be named Hannah) watches each of her sons being tortured to death in horrific ways rather than eat pork – and refuses to tell them to give in.

The story seems to acknowledge that there are secret Jews, but elevates martyrdom over continuity.

There’s a deep rift over who should be the high priest – a hereditary one or the person appointed by whoever is ruling over the territory at the time.

There is a lot of direct divine intervention.

You would expect that there would be a lot of prayers to God asking for success in battle, and there is. But beyond this, there are stories of more direct involvement by God.

At three different times, visions of men in gold, mounted on horses with gold bridles appear. Once, they flog an attacking general until he faints. Once, they flank Judah Maccabee to protect him, and those on the attack go blind and flee. Once, they appear in the air over Jerusalem for forty days, and the inhabitants are confident of their success in the impending conflict.

In what may be my favourite miracle of all time, one of the would-be conquerors is struck with “an incurable and invisible plague: … a pain of the bowels that was remediless came upon him, and sore torments of the inner parts;… So that the worms rose up out of the body of this wicked man… his flesh fell away, and the filthiness of his smell was noisome to all his army”, until “he himself could not abide his own smell”.

Reading Maccabees is challenging. Events are repeated. There are recurring names – Antiochus in particular is clearly a familial name; there are at least four. It is graphic and bloody. Jews don’t always behave nobly. There is a lot of conquest, defeat, conquest and defeat. When events recur, it’s not clear if they’re happening a second time, or if a story is being repeated with variations. Still and all, I encourage you to take the time to read it. You’ll come away with a deeper understanding of the Chanukah story, and a real sense of how fraught with tension and conflict that period of our history was.